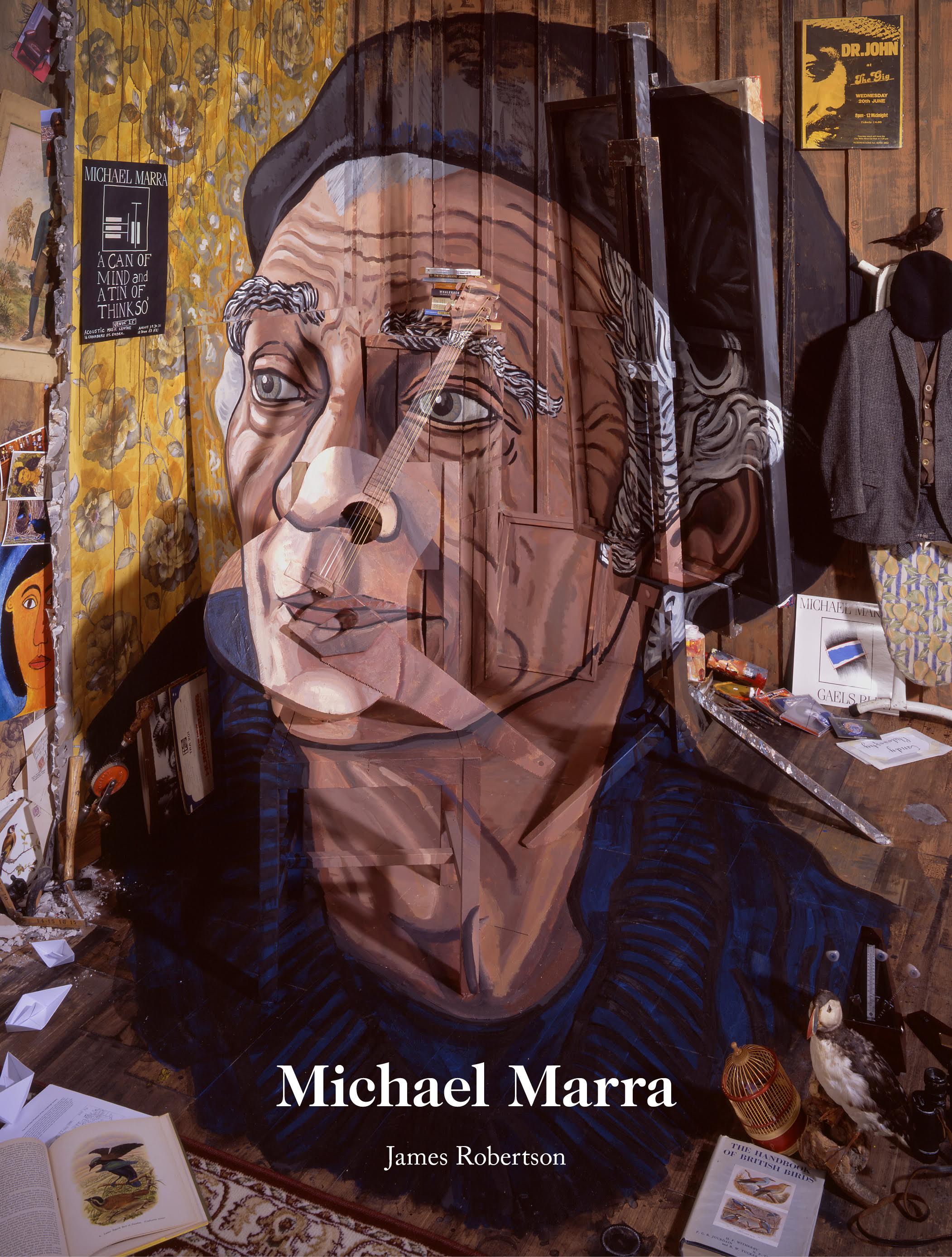

A fully illustrated 296 page biography by award-winning author, James Robertson, featuring original artwork, photographs and anecdotes from family and friends. Available in hardback and paperback.

Michael Marra (1952−2012) was the bard of Lochee, Dundee’s gravel-voiced chronicler of improbable encounters and real human truths, and also one of Scotland’s finest songwriters. Like Robert Burns, whom he greatly admired, Michael was driven by compassion, egalitarianism and a passionate hatred of injustice. His songs are loaded with humour, kindness, anger and profound intelligence. Above all, they celebrate the underdog and the extraordinary lives of ordinary people.

Over more than four decades, until his untimely death at the age of sixty, he composed hundreds of songs, including much-loved, idiosyncratic pieces of magic such as ‘General Grant’s Visit to Dundee’, ‘Frido Kahlo’s Visit to the Taybridge Bar’, ‘Mother Glasgow’ and ‘Hermless’ (often described as an alternative, nonviolent Scottish national anthem). He recorded six albums and several EPs of his own, and encouraged and produced the work of many others. He performed his music all over the world and collaborated with an astonishing range of musicians, including Martyn Bennett, the Average White Band, Patti Smith, Saint Andrew and the Woollen Mill, Mr McFall’s Chamber and The Hazey Janes, the band which includes his two children Alice and Matthew.

But Michael Marra had a concurrent, overlapping career in theatre, performing, writing and directing, working with poet Liz Lochhead and dancer Frank McConnell, and with Dundee Rep, Communicado and many other companies. He acted in film and on television, was an accomplished visual artist, wrote short stories and plays − and was always inspired, never restrained, by his deep attachment to Dundee, family, friends and − not least − football.

Impossible to categorise, allergic to fame, unimpressed by wealth or status, Michael Marra lived every waking moment as an artist, and touched all who knew him with his genius. In this book, packed with images and anecdotes some of which have never been in the public domain before, the many lives of this unique man are gathered together for the first time.

Buy the Book

Exclusive Extract...

Both Michael’s parents had a great appetite for music, which was part of daily family life: Margaret played piano and sang in both the Cecilian and Diocesan choirs; Edward did not play an instrument but loved jazz and classical music. Duke Ellington and Ludwig van Beethoven were Edward Marra’s great heroes: the only time Michael ever saw his father combing his hair was the night he went to see Ellington and his band play the Caird Hall in 1967.

One feature of the household, an item which in time Michael would inherit, was a very fine Blüthner piano. Edward had bought it for Margaret when a family friend, Charles McHardy (who himself played piano in a jazz band), spotted it for sale, couldn’t afford it himself, but alerted Edward to the fact that it was going for a reasonable price. Michael’s oldest brother Eddie learned to play on this instrument and passed on a few tricks to Michael. Michael learned mostly by ear and by accident, discovering ‘the good stuff’ through perseverance: ‘I love the shape of written music, but it looks like an adventure with Neptune rather than what [the notes are] supposed to convey. To me, the piano is all lying in front of you. It’s difficult to make a mistake as everything leads to something else.’

There were opportunities to learn to play music at school and, although money was tight, Edward Marra believed that music lessons were worth paying for. His understanding was that you learned music by a formal process of working your way up through the grades: Chris followed this path but Eddie and Michael took a more recreational route towards proficiency. When Michael was in his teens, Eddie brought home a guitar for him and Chris. Both of them were interested in learning how to play it, taking their cues from the likes of James Taylor and Joni Mitchell. But while Chris would become a professional musician, for Michael instruments were always only a means to an end; and the end was to write songs.

If Edward was willing to pay for music tuition, Margaret paid – on the ‘never-never’, which Edward did not approve of – for some of the instruments the boys wanted out of Larg’s Music Shop in Whitehall Street. (However, as Chris Marra remembered, ‘It was my Dad who lled in the H.P. forms for my guitar and amp, the only debt he ever took on. Even at a young age I could understand how it must have pained him to go against his principles for my benefit.’) On one occasion, when Margaret was in Larg’s with a friend, a demonstration was being given on a baby grand piano. As they listened, a salesman spotted them and asked if they were interested in the piano. Margaret explained that she already had a piano at home.The salesman said it could be traded in and asked what make and model she had. Margaret described the Blüthner and asked if that would be good enough. ‘Madam,’ he replied, ‘I think we would be giving you money on such a trade-in.’ When she got home, the stacks of National Geographics and other items were cleared from the top of the piano and it was given a good polish.

There was always singing in the Marra household. The range of music to which the children were exposed at home was wide and inclusive, from Uncle Mac’s Children’s Favourites on Saturday morning radio to opera and much in between...

Michael absorbed everything, from hymns sung at church (the melody of ‘Soul of My Saviour’ would find its way into the opening bars of Michael’s ‘Mother Glasgow’) to Elvis Presley – ‘Jailhouse Rock’ was his earliest, indelible musical memory. The Beatles impressed not just because of their energy and enthusiasm but because they wrote their own songs. In fact, Michael said, it was John Lennon who ‘forced’ him to be a songwriter: ‘his voice was more than language.'

The Beatles seemed almost American, coming in on a big wave that also contained early Motown – the Four Tops, Stevie Wonder, the Temptations and others. Dundee responded at some deep-seated emotional level to soul music – ‘the Dundee disease’, Michael called it. Maybe this was explained partly by the city’s long history of being sneered at, denigrated or just ignored by people elsewhere who thought themselves culturally superior: ‘I think of Dundee being like a sort of black ghetto of Scotland. I read the columns in the Scottish papers, the Herald and the Scotsman and so on, and the journalists are always ready with a snide remark for Dundee.’

Bob Dylan also made a huge impression on Michael. He wrote lyrics full of literary allusions and packed words and rhymes into melodies in a way that was totally ground-breaking. When Michael first heard Dylan’s voice, he assumed it belonged to an old man. That such songs were being made by a man in his twenties was both a revelation and an inspiration. Years later, in the notes to his song ‘Bob Dylan’s Visit to Embra’ on Posted Sober, Michael wrote:

This is my wee tribute to the great man and was written so that I could use a mouth organ and harness which was given to me by my son Matthew. Bob’s sixtieth birthday is approaching and I’d like to celebrate, maybe a gig with Bob’s songs for the whole night would be good. When I first heard him I thought he was an old man. I would have been about ten or eleven. I was pleased when I saw his photograph (with Suzy Rotolo) because he looked young and he was wearing jeans, then I thought he must be the coolest and most wise young man on the planet. AND he had a girlfriend. I loved the way people put their faith in his vision and took him seriously while enjoying the landscape of his imagination. Dylan sang directly to me, that song-writing was huge, that nothing should be discounted, big songs, ‘Masters of War’ and ‘Hard Rain’, ‘Ramona’. Personal and political.

Michael first publicly articulated his long-term ambition to be a songwriter while still at St Mary’s Primary School in Lochee. A group of boys in his class were discussing what they wanted to be when they grew up, and he said he wanted to be a songwriter. As the others mostly intended to have glittering football careers, this was not a popular option, in fact he expected derision, but then another boy, John Duncan, chipped in, ‘My uncle’s a songwriter.’ This assertion too was met with a degree of scepticism. ‘Oh aye. And who is he?’ ‘Stephen Sondheim.’ None of them had heard of Sondheim or West Side Story (the show opened on Broadway in 1957), but it turned out that John Duncan was telling the truth. ‘The mere fact that somebody had a relation who wrote songs as a job was impressive: it was a big thing for me.’

- Written by James Robertson

- Designed by Andrew Forteath

- Project Management by Anna Day

- Project originated by Bryan Beattie

- Printed by Bell and Bain